Preservation Is about More than Saving Buildings

It depends on getting the street right.

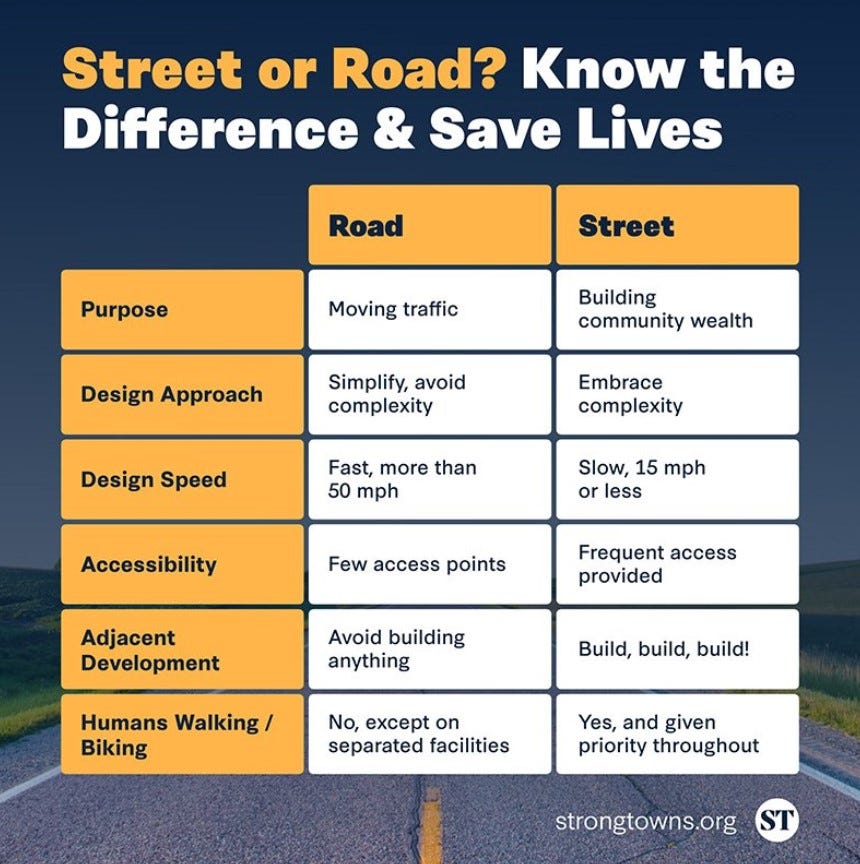

For many years, the Downtown Mobile Alliance has been a strong advocate for the concept of “walkable urbanism.” Before that, it was Main Street Mobile singing that song. Today, the City is a keen advocate for designing the street to fit the adjacent built environment. The city’s leadership, from Mayor Stimpson to engineers Nick Amberger and Jennifer White, knows that the type of street design that works downtown is very different from the street design that works in the suburban style of land development. This is great for Mobile!

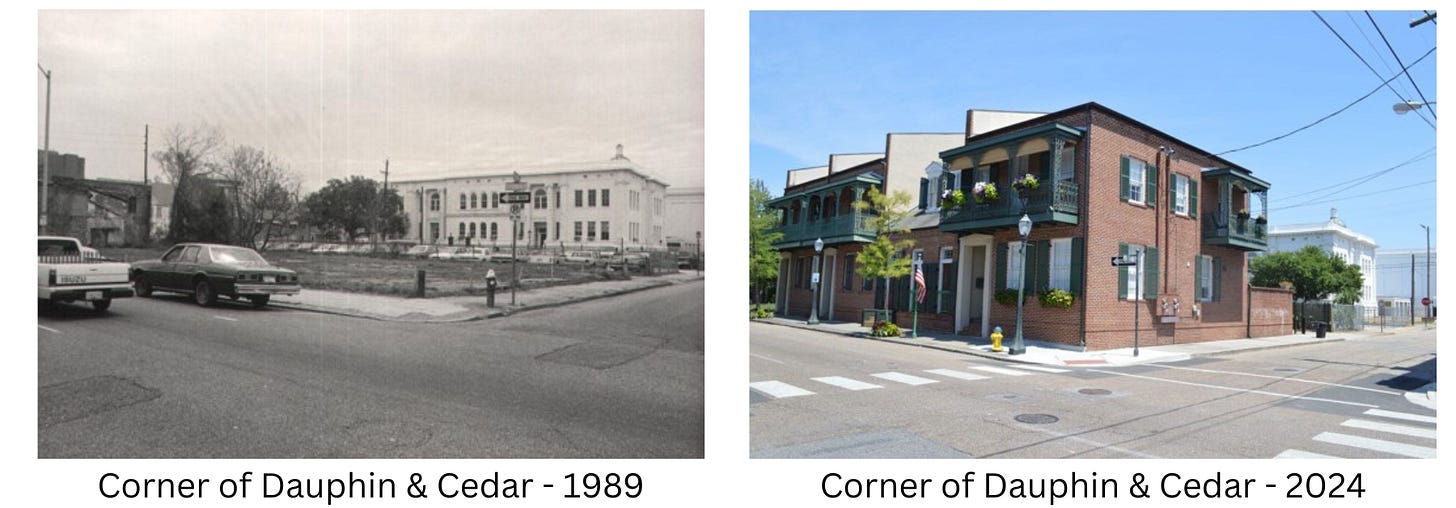

In 1990, Dauphin Street was a frictionless two-lane speedway for suburbanites heading to the office buildings along Royal Street. St. Francis Street was a frictionless speedway out of downtown and towards west Mobile neighborhoods. The buildings along both streets were struggling economically, if they were still standing at all. Because the street functioned incorrectly, the adjacent buildings were not economically viable.

The sidewalks on Dauphin Street were unhospitable. In fact, they were free of everything: trees, café tables, window boxes, retail displays, planters, etc. This meant that the sidewalks were free of people lingering and enjoying the casual interactions that happen on well-managed sidewalks on people-friendly streets. What lined the sidewalks were interstate-level cobra-head light fixtures that projected light onto the street and not the sidewalk. This meant that the sidewalks were dark in the evening. None of this was good for the economy of downtown – neither the businesses nor the building owners.

Quickly, Main Street Mobile began advocating for on-street parking on Dauphin Street, which was put in place around 1991 or 1992. That row of steel protective devices, also known as parked cars, along with the reduction of travel lanes instantly made the street feel safer. (The sidewalks had been widened in the late 1970s, but because the street continued to prioritize cars, the effort was an expensive public works project without the intended effect.)

Retailers continued to struggle, but a transition was happening. With Dauphin Street’s vehicles moving more slowly, a young group of F&B entrepreneurs opened eateries and music venues. Then, with the street calmer, business owners wanted sidewalk cafes. Again, city leadership embraced the sidewalk café concept while enacting little regulation, and the sidewalks and streets began to be filled with people.

How does this connect to Preservation Month or even the present day? When the areas streets and sidewalks function in a manner that attracts pedestrians, historic urban buildings, or even new buildings built in the urban style, have a very different economic opportunity.

Just look at St. Louis Street. St. Louis Street was made two-way during Mayor Sam Jones’ administration. The street’s buildings were in a serious state of decline at that time. Slowly, some might say too slowly, the buildings began to transition from warehouses to new uses like apartments, offices, event planning, antiques, dining, and finally an upscale grocery. This would not have happened if the street had not been designed to strike a balance between humans and vehicles.

Is there more work to be done in St. Louis? Yes, and the city is on the cusp of a major public works project to take St. Louis to the next level.

A very important action the city can take to rapidly move downtown to the next level is the full implementation of the Optimizing Downtown Streets for Safety and Development study that Jeff Speck and Main Street Mobile released in 2021. The city embraced the study and engaged Volkert to produce the street-by-street construction documents to implement the plan. Those documents are complete. Implementing the improvements is specifically named in the Tax Increment Financing District renewal document of 2023. Already, the traffic signals around Bienville Square have been replaced with time- and pollution-saving all-way stop signs. Most of the recommendations are quick, inexpensive changes like this. Speck’s goal was, “What improvements to the function of the street will have the greatest impact for the least amount of money?” Are there public works improvements recommended? Yes, the removal of the pedestrian-frightening slip lane (a lane that allows a right turn without stopping) at Dauphin and Water streets is an example.

Implementing Speck’s recommendations will be good for business, good for property values, and good for preservation efforts for Downtown Mobile’s many historic buildings. The preservation community should rally behind the implementation of Speck’s recommendations and then advocate for a similar ethos to guide street design in the other historic districts.

Elizabeth P. Stevens

President & CEO Emeritus